Functional Sets, Part 4: Recursive Membership and Size

Now that our trees balance themselves we’ll continue building the rest of the set API on top of them. This week, we’ll answer two questions:

- Is an item in the set?

- How many items are in the set?

We’ll need to write some more recursive functions to get these to work, and they’ll show us two different styles of recursion!

Quick Recap

Our sets are AVL trees (a kind of binary search tree) under the covers. We’ve modeled this data structure in our Elm code like this:

type Set comparable

= Tree Int comparable (Set comparable) (Set comparable)

| Empty

We can create empty sets using empty, sets with a single item using singleton, and bigger sets by using insert or fromList.

Membership / Contains

It’s one thing to be able to store a set, but it’s not much use if we can’t tell what we’ve stored. What would we want that API to look like? How about a function that takes an item and a set and returns a boolean value indicating if the value is in the set?

oneThroughFive : Set Int

oneThroughFive =

fromList [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

member 5 oneThroughFive == True

member 8 oneThroughFive == False

The core API for sets calls this function “member”, but it sometimes makes more sense to call it “contains”. Think of it however makes the most sense for you. Anyway, here’s how we’ll implement it:

member : comparable -> Set comparable -> Bool

member item set =

case set of

Empty ->

False

Tree _ head left right ->

if item < head then

member item left

else if item > head then

member item right

else

True

This function recursively walks down the tree until it either finds a value or an empty set. At each level, we see if the value is less than or greater than the head, and proceed with the relevant subtree.

We also define two base cases:

- If the head is empty, it definitely doesn’t contain the value we’re looking for.

That means we should return

False. - If the item is neither less than nor greater than the head, that means it’s equal to the head!

In this case, it’s in the set, so

True.

But here’s the interesting thing about this function: the recursive cases are only recursive. They don’t hold onto or combine values from their recursive calls in any way. This gives us a pleasant property called tail recursion, in which the Elm compiler can optimize this to work for any size set without running out of stack space.

Lost and Found

Let’s visualize how this works.

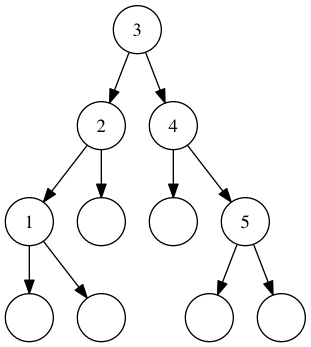

Given oneThroughFive, we want to find if 5 is in the set:

A set containing the numbers 1 through 5.

First, we’ll look at the head.

We’re looking for 5, and it’s greater than 3 (the head), so we’ll look in the right subtree.

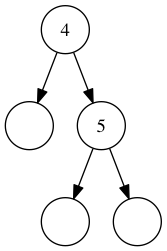

A set containing the numbers 4 and 5.

Same thing here.

5 is greater than 4, so go right again.

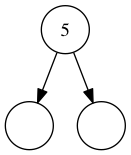

A set containing only 5.

This time, the head is 5 and our item is 5.

They’re equal, so our code returns True.

This bubbles up to tell us that 5 was indeed in this set.

Lost and… Lost?

But what happens when we search for a value we don’t have?

How about 8?

We’d take exactly the same path as before, except where we returned True we’d see that 5 and 8 are not equal so we’d recurse down the right tree.

An empty set.

When we got there we’d find that the subtree was Empty and return False.

How Big is Our Set?

Next, let’s figure out how many items are in our set.

For oneThroughFive the answer is 5.

We’ll call this new function size.

size : Set comparable -> Int

size set =

case set of

Empty ->

0

Tree _ _ left right ->

1 + size left + size right

So what are we doing here?

Remember how in member we only ever returned a value, and never modified it on the way back from our recursive calls?

Well, sometimes we have to!

Otherwise, how would we add?

When we have a non-empty set, we know it at least has one item in it.

So we’ll say “I have one, plus however many items are in my left and right subtrees.”

Then we do the same thing for each subtree, recursively, until we have nothing but Empty trees.

Let’s trace this execution to get a sense for how it should work.

If we do fromList [8, 15], we’ll get a set that looks like this.

(I’m blanking out the heights; they’re not important here.)

Tree _ 8 Empty (Tree _ 15 Empty Empty)

When we call size eightAndFifteen, we can substitute the subtrees for our addition:

1 + size Empty + size (Tree _ 15 Empty Empty)

The left subtree will come back with 0, so we’re left with:

1 + 0 + size (Tree _ 15 Empty Empty)

And replacing the second size call:

1 + 0 + (1 + size Empty + size Empty)

Again, we know that empty sets have size 0, so:

1 + 0 + (1 + 0 + 0)

We eventually return this set has 2 members, which checks out. Yay!

When you’re working with recursive functions, it can help to write out the values one step at a time. You’ll see exactly where your logic might be breaking down. It’s a very handy debugging tactic!

But it also shows us that this function isn’t tail recursive: it has to hold on to values to add. There are ways to write this tail-recursively, but for now it’s fine to just be able to tell the difference. In general, if your function has to hold onto state from recursive calls, it won’t be tail recursive, and won’t be as highly optimized as an equivalent function that is.

Done!

So now we have two more tools in our Set toolbox: member and size.

And you have two more tools in your recursive function debugging toolbox:

- Start with the base case first

- Write out and substitute calls step-by-step to debug.