Functional Sets, Part 5: Folds

We’re in the middle of a quest to build a set implementation from scratch. So far, we’ve implemented our constructors, rotation, balancing, size, and member. Last week we stopped off to review how folds work. This week, we’re going to create folds for our set!

Ready, Set, Fold!

Remember that the signature of List.foldl:

foldl : (a -> b -> b) -> b -> List a -> b

We’ll mimic this with our implementation of foldl:

foldl : (comparable -> a -> a) -> a -> Set comparable -> a

First, and most obvious, we’re accepting a Set instead of List.

This makes sense, but why comparable?

Well, since we compare values to construct our set, it always has to be comparable.

And, in this case, we wouldn’t strictly need to accept comparable, but we should for consistency’s sake.

But this raises a question… What does it matter if we fold left or right in a tree? How do we walk left to right or right to left in our implementation?

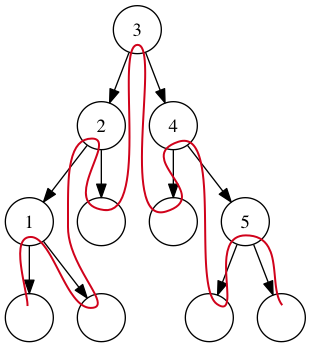

I didn’t know, so I asked Rebecca Skinner. She drew this on the whiteboard:

Walk order in a tree (with apologies to Rebecca, whose drawing was much nicer.)

All we have to do is follow that red line to get the proper walk order.

To put foldl in words: if we have an empty set, we return the accumulator.

If we have a tree, we fold the whole left branch recursively, then the head, then the right branch recursively.

When we call that on our tree of one through five, rooted at three, we’ll recurse down the left branch first. When we hit the subtree rooted at two, we’ll recurse down the left side of that, and then do the same for one. The left subtree of one is empty, so we’ll fold the head, then the right subtree (which is also empty.) At that point we’ll pop back up a level, fold the head of two, then the right subtree there. We continue going up and down like that until we’ve traversed the whole tree.

When we want to foldr instead, we’ll go in the opposite order.

We’ll start with the right subtree, then the head, then the left subtree.

I’ll let you trace that line yourself; it works the same way.

If all that seems confusing, remember that we’ll be operating on one case of our union type at a time. But it helps to have the bigger picture of what the code is doing in your head before we begin.

Folding Sets, For Real

Now let’s write some code!

Let’s do foldl first.

foldl : (comparable -> a -> a) -> a -> Set comparable -> a

foldl fn acc set =

case set of

Empty ->

acc

Tree _ head left right ->

let

accLeft =

foldl fn acc left

accHead =

fn head accLeft

accRight =

foldl fn accHead right

in

accRight

Our cases look pretty much how we described them above. We start with our empty case, where we return the accumulator unchanged. Easy enough.

Our Tree case is more complex.

We’re doing recursive calls here, and to make it easier we give them names in a let statement:

- First we’re calling

foldlon the left subtree. This will walk down all the left trees in the set until it finds an empty node. - Next we process the head. This is different, because it’s a single value. No recursion necessary, but we’ll use the result of the last fold as the accumulator value in the call.

- We’ll finish things off by doing the same operation we did on the left subtree on the right. But in this case, we’re passing in the accumulated value from the head.

Finally, we return this accumulated value.

When we implement foldr, we do these three things in the reverse order: right first, then head, then left.

Try tracing out these calls, and you’ll find that they happen in the same order as the line in the graphic above.

Let’s Fold Some Stuff!

We’ll start off simple. Let’s sum up a set of numbers:

foldl (+) 0 (fromList [1, 2, 3]) -- 6

This does exactly the same as List.fold, except we’re using Sets.

We’ve taken all the values from our list, added them to the accumulator, and got back a result.

Folded!

How about something more complex?

Remember how we implemented member and size as recursive calls before?

Now we can use foldl to do the same thing!

Size

size shrinks drastically when we redo it with foldl (down from 7 lines to 3):

size : Set comparable -> Int

size =

foldl (\_ acc -> acc + 1) 0

Our combiner function ignores the value that’s in the set, and instead increments the accumulator value. This is exactly what we were doing before, but now we can express it much more succinctly.

Notice we’re also doing this in point-free style!

Since we’re not providing all the arguments to foldl, it’s curried into the function we want.

We could also implement size like this:

size : Set comparable -> Int

size set =

foldl (\_ acc -> acc + 1) 0 set

I prefer the point-free style, but do whatever makes sense to you.

Member

member is somewhat more complex:

member : comparable -> Set comparable -> Bool

member item set =

foldl (\candidate acc -> acc || (candidate == item)) False set

Here we start out with the accumulator value as False.

We assume that if we never find the member, the value will always be false.

Our accumulator function takes the candidate and the accumulator. The notation here says “return the accumulator value if it’s true, otherwise the equality value of the candidate and item we’re searching for”. Yay for boolean logic!

But this implementation has a problem.

The member implementation we wrote before only had to check a few values as it made it’s way down the tree.

Because we’re using a binary search tree, it should only have to look at log(n) items, where n is the size of the tree.

But this new implementation looks at every value.

That means it has to look at all n items in the tree.

That may not seem like a significant difference, and in the size trees we’ve been working with, it isn’t.

But when we have trees with many items or values which are expensive to compare this difference blows up in our faces.

If we have a set with a thousand values in it, our old implementation would only have to look at 10(ish) values.

But if we do it with a fold we’ll have to look at all 1000!

This tells us that while folds are useful, they’re not suitable for every function.

Folds: Done!

So we’ve seen:

- How to implement

foldfor binary search trees (and thus, for our set) - How to reimplement some work we’ve done to be more clear by using

foldlorfoldr - When folds work well (when you’ve got to consider every value) and when they don’t (when you only want to consider some.)

Now that we’ve written folds, we can get into even more mischief. Next time, combining sets and removing items!